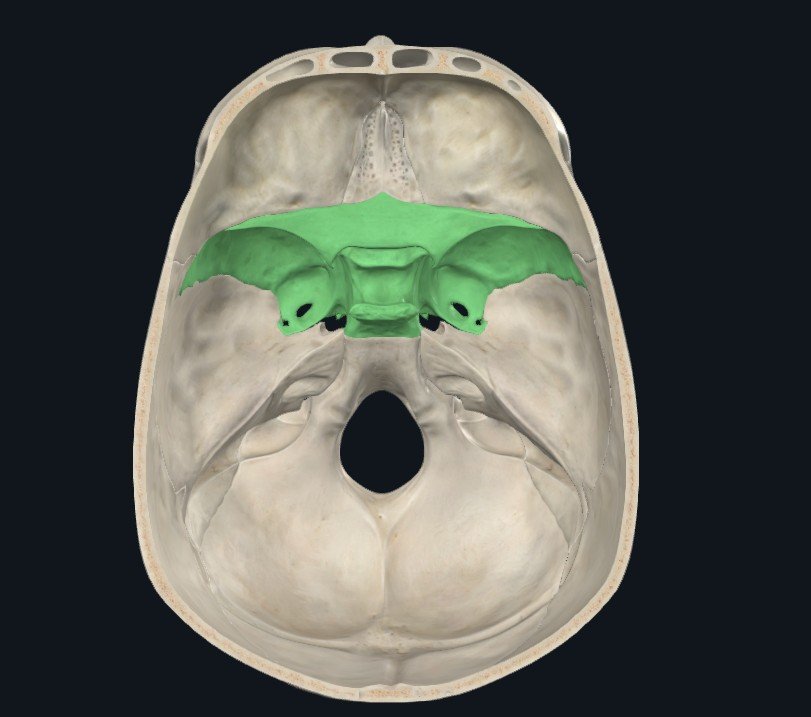

The sphenoid is a moth-shaped cranial bone that sits behind the eyes in the center of the head. “Sphenoid” comes from the Greek word “sphenoeides” meaning “wedge-shaped.” This wedge in the center of the head connects with each cranial bone, allowing the sphenoid’s rhythm to influence the movement of every other cranial bone. The sphenoid is related to our nervous, muscular, fascial, hormonal, and vascular systems. Bringing the sphenoid bone back to a normal craniosacral rhythm pattern can alleviate many symptoms associated with these systems. Most clients I see need some work with the sphenoid.

We’ll discuss the anatomy and physiological systems, possible associated symptoms, and treatment in this blog.

Soft Tissue Attachments

mandibular (Jaw) movement

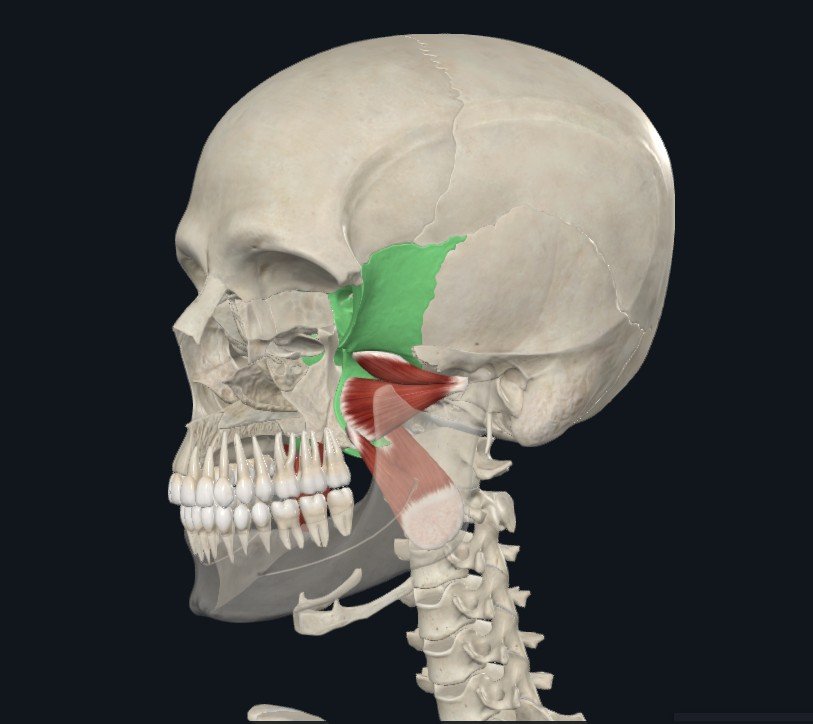

The sphenoid has muscular attachment points for muscles related to jaw movement, chewing, swallowing, and hearing. The medial and lateral pterygoid muscles (shown below) attach the mandible (jaw) to the sphenoid. The lateral pterygoid also has some attachments to the temporomandibular disc, meaning restrictions in these muscles can contribute to temporomandibular joint pain and difficulty with opening the mouth and chewing. Treating the sphenoid along with the temporal bones, mandible, and maxilla are an important components of treatment.

swallowing Movements

Palatine aponeurosis

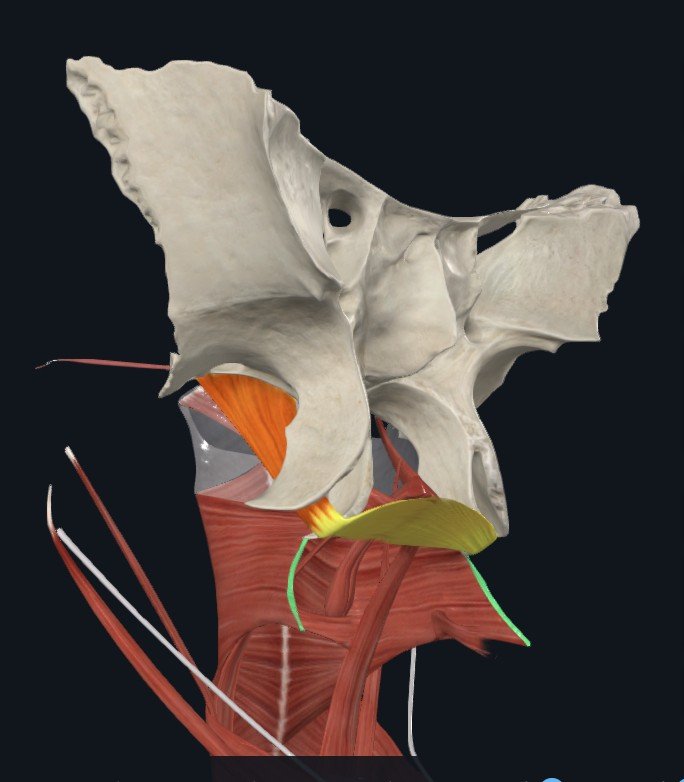

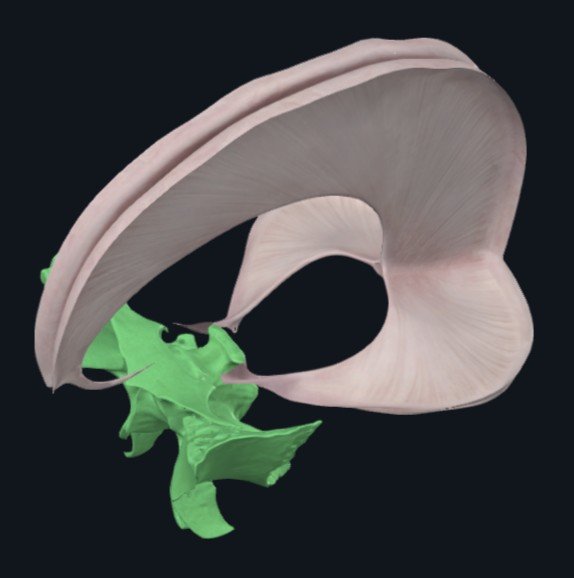

The palatine aponeurosis and pteygomandibular raphe are connective tissue structures that connect the sphenoid to many of the muscles involved in swallowing. The palatine aponeurosis is a strong tendinous connection extending from the tensor veli palatini muscle. The tensor veli palatini muscles (there is a right and left side) originate on the scaphoid fossa and spine of the sphenoid as well as the wall of the auditory tube. From there, they extend down towards the mouth and the tendinous connective tissue wraps around the pterygoid hamulus at the bottom of the medial pterygoid plate of the sphenoid. This tendinous tissue between the pterygoid hamulus is called the palatine aponeurosis, which is an attachment point for the following muscles involved in swallowing:

- Levator veli palatini

- Palatopharyngeus

- Musculus uvulae

- Palatoglossus

The tensor veli palatini muscle itself contributes to swallowing. Additionally, it also helps regulate pressure in the middle ear by opening the auditory tubes.

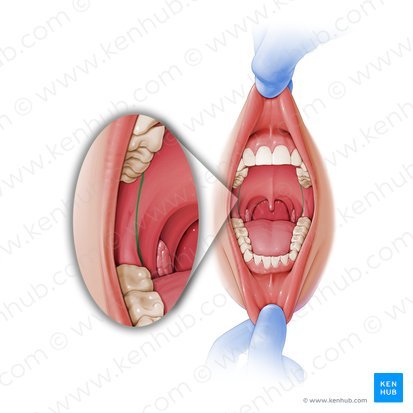

pterygomandibular raphe

The pterygomandiubular raphe is a connective tissue that connects the sphenoid and mandible bones. It also provides at attachment point for two important muscles: the superior pharyngeal constrictor (swallowing) and the buccinator (chewing). The raphe is easily visualized in the back of the mouth and is also an important landmark for dental procedures and nerve block injections (1).

Restrictions in these muscles of chewing and swallowing can impair normal movement of the sphenoid. And abnormal movement of the sphenoid can impact the muscles and actions of chewing and swallowing. The sphenoid, mandible, maxilla, palatine, and hyoid bones would be particular areas of focus during Craniosacral treatment.

hearing

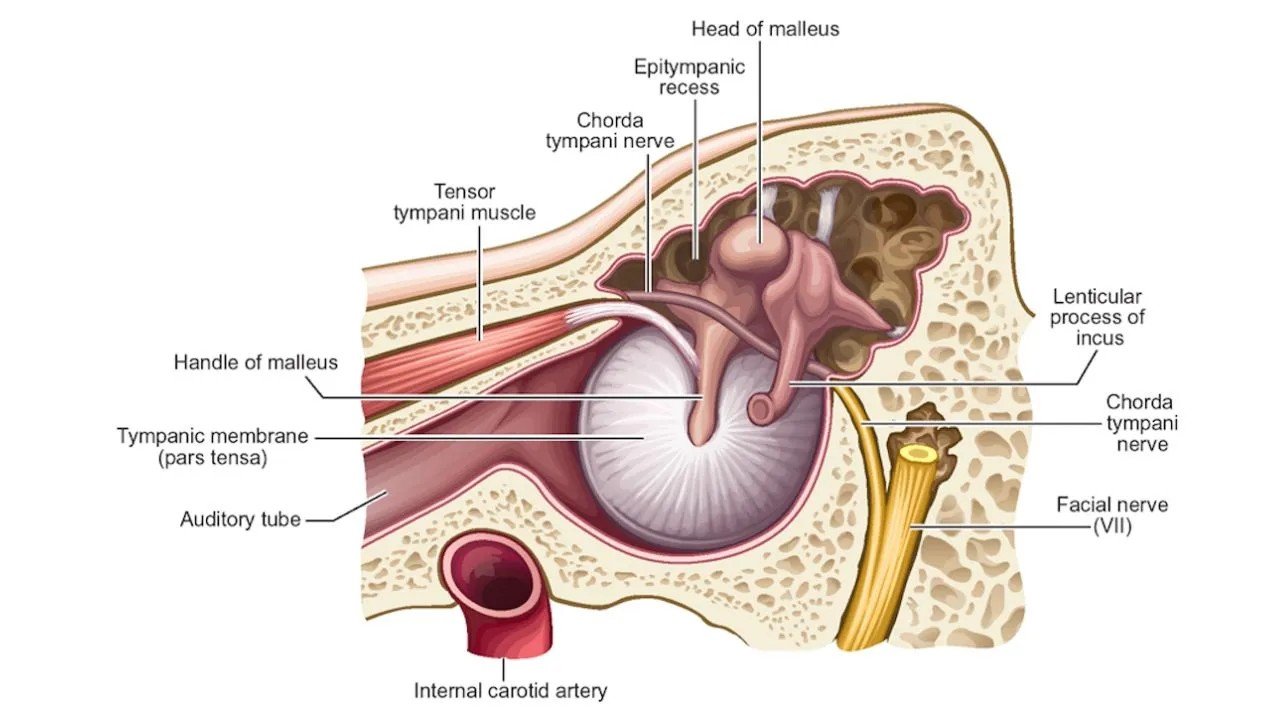

The tensor tympani muscle (image 3 and 5) is involved in hearing. It originates on the sphenoid bone and inserts on the malleus, a small bone in the middle ear. The tensor tympani helps to protect the middle ear by tightening the tympanic membrane (ear drum) in response to loud sounds. If the tensor tympani is not functioning appropriately, it may contribute to tinnitus, hearing loss, hyperacusis, and vestibular issues (3). Craniosacral sessions may focus on the sphenoid and temporal bones.

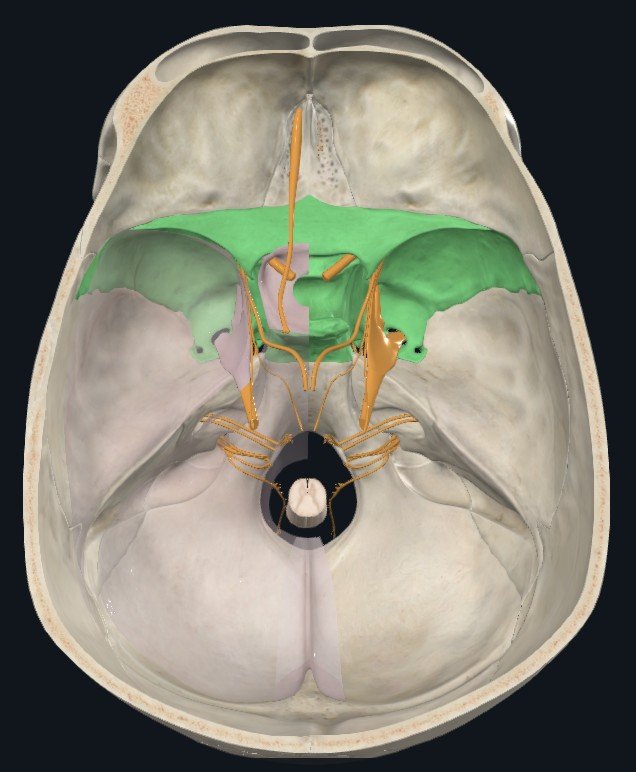

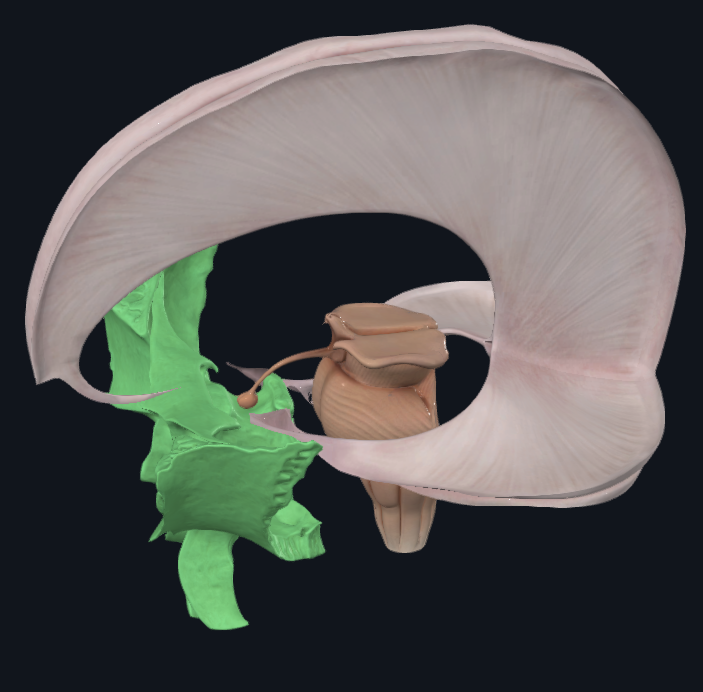

Intracranial Membrane

The intracranial membrane is composed of dura mater, the outermost layer of tissue surrounding the central nervous system. Dura mater (“tough mother” in Latin) provides protection for the brain and spinal cord. In the skull, it also folds into layers that create the intracranial membrane system. These layers of tissue separate lobes of the brain, provide support, and create channels for the venous system to run within the cranium. The outer layer of the dura mater is firmly attached to the cranial bones. The tentorium cerebelli of the inner layer also attaches to the sphenoid bone (image 6).

Treating the sphenoid bone may affect the tentorium cerebelli, improving blood flow, cerebrospinal fluid flow, and overall health and function of the brain.

Cranial Nerves

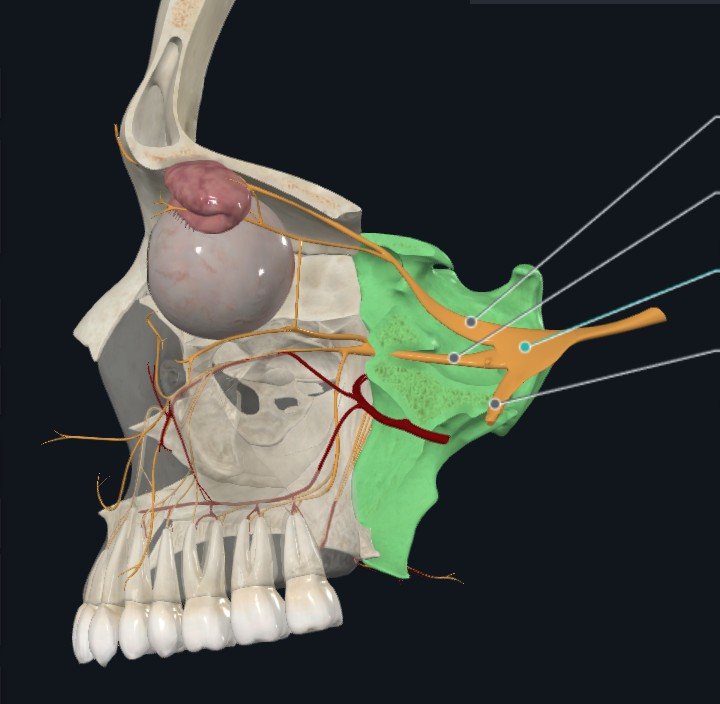

The sphenoid bone foramen (openings) allow several cranial nerves to extend from the brain, through the skull, and to the eyes, teeth, and facial muscles. The optic, opthalamic, trochlear, trigeminal, and abducens nerves all pass through openings in the sphenoid. These nerves control chewing motions, eye movements, and sensations of the eyes, teeth and face. Treating the sphenoid may assist in the function of these nerves.

Pituitary Gland

The sphenoid also creates space for the pituitary gland. This small, pea-sized gland is referred to as the “master gland” because it secretes hormones that regulate other glands and organs. The pituitary sits in a saddle-shaped structure in the sphenoid bone called the sella turcica. It receives information through hormones and nerve impulses from the hypothalamus, which it is attached to via the pituitary stalk. The pituitary gland releases several hormones that help regulate the hormone production of the thyroid, adrenal glands, and the reproductive organs. These influence growth, metabolism, salt/water balance, physiological stress response, lactation, and labor and childbirth (5).

Craniosacral Therapy Impact

Craniosacral Therapy can help people experiencing a variety of symptoms. One way this occurs is by reducing physiological stress to allow the body to access resources for healing. Craniosacral Therapy also influences the movement of anatomical structures and may assist nearby structures to improve their function. This can be easily observed and felt in cases that involve the muscular system. An example would be treating the sphenoid bone and then palpating a decrease in muscular tension in the lateral pterygoid that helps to reduce symptoms of jaw pain. In other cases, like pituitary gland function, we may not be able to observe or measure an immediate impact from Craniosacral Therapy. Knowing the anatomy around treatment areas, however, can help us to understand the potential impact.

references

- Vutukuri R, Kitagawa N, Fukino K, Tubbs RS, Iwanaga J. The pterygomandibular raphe: a comprehensive review. Anat Cell Biol. 2024 Mar 31;57(1):7-12. doi: 10.5115/acb.23.232. Epub 2024 Jan 30. PMID: 38287643; PMCID: PMC10968190.

- https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/pterygomandibular-raphe

- Sutton AE, De Jong R, Kwartowitz G. Tensor Tympani Syndrome. [Updated 2025 Jul 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519055/

- https://treblehealth.com/nitropack_static/qSItAAKlROyJYNmUhlpIgcUGZpCFmgPs/assets/images/optimized/rev-e6df8f6/treblehealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Newsletter-images-3-1.jpg

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21459-pituitary-gland

Leave a Reply